Amazon, Mindsets, and Resiliency

Fewer brains, fewer options, and more fragility — the era of consolidation carries risks

Remember the saline shortage of 2018? After Hurricane Maria devastated Puerto Rico, the supply of life-saving saline for US hospitals was severely threatened. It was covered in NEJM at the time, with the authors noting that saline wasn’t the only vulnerable resource on the medical market:

Most drug shortages occur with older, generic, injectable medications that are produced by a small number of suppliers — typically three or fewer. The United States gets its saline from just three companies: Baxter International, B. Braun Medical, and ICU Medical. . . . when one supplier experiences a shortage, other suppliers often have insufficient manufacturing capacity to make up the difference. Drug manufacturers are not required to have redundancy in their facilities or even a business contingency plan in case of a disaster, no matter how essential or lifesaving the medication they are producing.

Consolidation has hit every industry. Eyeglass manufacturers? Mainly one in the US, operating under numerous brands. Con-Ag companies? Two or three. Four companies — General Mills, Post, Quaker Oats, and Kellogg’s — own about 85% of the cereal business in the United States. Radio broadcast networks? Meat producers? Overnight logistics? Airlines? Cloud providers? A few options in each case, at best.

Consolidation has fed corporate success for decades. It trims waste — otherwise known as jobs — and increases market heft. At the same time, a reliance on just-in-time manufacturing and delivery has made for a more fragile supply chain.

Perhaps no corporation reflects the power to be gained by consolidation more than Amazon. In 25 years, this company has gone from a bookselling e-commerce startup to one of the world’s richest and most dominant companies. From Audible to Whole Foods to IMDB to Zappos, Amazon has scooped up plenty of businesses over the years. And it has created advantages with consumers through clever and appealing offerings — for instance, a full 82% of American homes subscribe to Amazon Prime, more than put up a Christmas tree or watch the Super Bowl.

So when Amazon’s founder and CEO, Jeff Bezos, announced yesterday he is stepping away from the CEO role even as his company announced record earnings ($125.56 billion last quarter), it seemed a good time to talk about where the past 25 years have brought us more generally.

And how trends toward a smaller number of players in a market can limit our thinking.

In scholarly publishing, we’ve consolidated among both producers and purchasers.

Consolidation among producers is a tendency toward monopoly, and provides structural power which can manifest as financial influence, cultural influence, or political influence. It means 100 decision-makers of the past may have become 10-15 now.

Consolidation among purchasers is a tendency toward monopsony, which can have similar effects by constraining the range of options for producers, who are in the thrall of a few select buyers, who may have a common view of how the market should behave.

No matter which side of the table consolidation occurs, it has one effect that isn’t often described — consolidation reduces the number of brain trusts involved in strategizing, thereby placing a definite limit on the imagination, experience, and experiments in a market.

The notion of fewer brain trusts as a hidden vulnerability emanating from consolidation first hit me as I listened to a 2015 interview with country music superstar Vince Gill. In his conversation with Dan Rather, Gill was asked why country music — founded by both men and women, and with standout female artists like Loretta Lynn, Dolly Parton, Reba McEntire, Martina McBride, Dottie West, The Judds, Pam Tillis, Rosanne Cash, Patty Loveless, Emmylou Harris, Trisha Yearwood, Crystal Gale, Tanya Tucker, Barbara Mandrell, Tammy Wynette, Patsy Cline, and Shania Twain — has become male-dominated over the past 10-15 years.

Gill had this to say:

I look at the history of this music, and you have just as many inspiring female artists who did as much for this format as men ever did. And for my favorite artists as I look back, I’m probably going to pick more women than . . . men. In my viewpoint, they’ve consolidated our industry just like every other industry in our country. . . . The consolidation . . . is I think a big reason for it. . . . You’ve trimmed the opportunities down by quite a bit. . . . When I was making my first records in the early 1980s, there were about 35 record companies that were runnin’ and gunnin’ and making an impact in our industry, and now there’s three or four. If there’s only three or four brain trusts. . . . If you only have three or four mindsets, what does that do?

Gill is seeing one slice of the general consolidation of American media — and American life — that has occurred over the past 30-40 years. Along with it has come a reduction in the number of mindsets participating in the space. And, with fewer perspectives, fewer points of view, and more “playing it safe” to protect the status quo, the result is a regression to the mean.

In country music, it has resulted in a regression to the men.

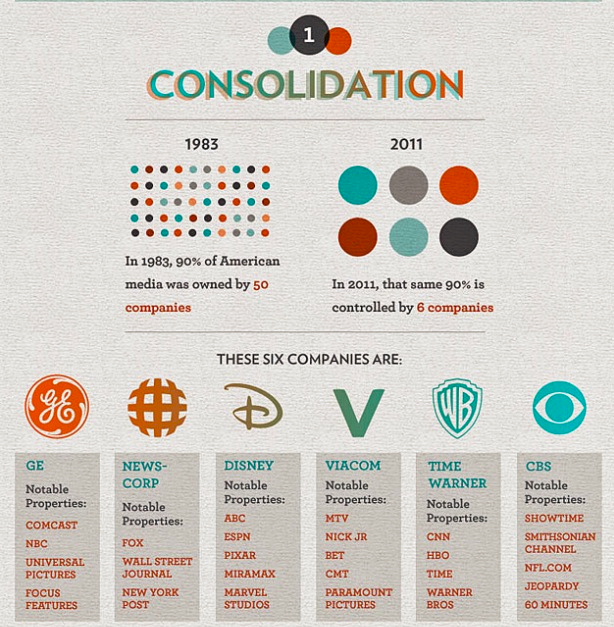

The change is stark. Between 1983 and 2011, 50 US media companies had become six:

In 2014, this number almost fell to five, as News-Corp made an $80 billion play for Time Warner — a tender Time Warner declined.

The same has occurred in our space. Hosting providers? Really two or three at this point. Contract publishers? Better numbers, but it seems a fragile count. Editorial services options? Conversion houses? A low number of options in most cases. This year has seen an explosion of possible virtual meeting providers, but that number is bound to shrink as cost pressures and market experiences lead to consolidation.

On the purchaser side, we’re seeing even more consolidation. First, we transitioned from tens of thousands of individual and academic department subscribers to a few thousand institutional subscribers. These institutions consolidated to some degree via consortia. Now, funders and governments may consolidate the purchasing side even more, as a single idea — open access — rationalizes their purchasing programs. They’re buying services now, which gives them negotiating power. Look at the power one ad hoc body — cOAlition S — has had on scholarly publishing if you want to see how a few entities posing as purchasers can bring an industry to heel.

This occurred to me as I perused the current issue of Learned Publishing, which is themed on the idea of “resiliency.” Scanning the articles, authors generally define resilience as being achieved via standards, openness, transparency, and trust.

Yet, we don’t often talk about “diversity” and “resilience” in business terms. The era of consolidation has brought about economic inequality, and revealed fragility in our supply chains and social structures. In calls for resiliency and inclusion, I have yet to see a call for more market participants, more buyers, lower profit margins, and more well-paid staff to provide living wages to a greater swath of people in more places. There are no calls for anti-trust enforcement or reduced business consolidation. Nowhere is there a plea for scholarly publishers to start branches or businesses in cities like Edmonton, Phoenix, or Cardiff, so they get out of their metropolitan bubbles. There’s no call to rethink the trend toward lower-wage workers, outsourcing, or faster production times at the expense of quality. Instead, the focus is on personal and social resiliency — can we bear the burden? — and not structural or economic resiliency.

When you layer on top of this that one small purchasing coalition — Plan S — can reshape an entire industry, the fragility of our consolidated market becomes all the more apparent. Thanks to consolidation, cOAlition S had fewer minds to change, fewer minds to convince, and fewer minds pursuing divergent or countervailing strategies to mount meaningful objections. Of course, Plan S has led to even further consolidation, deprecating even more mindsets and worldviews. It’s a vicious cycle.

Will we respond to the mounting challenges with plans for true economic resiliency and market robustness, and the appropriate investments and strategies? Or simply talk about how well we coped with the cards we were dealt by a few powerful players?