AOC, Drugs, Risk, and Publishers

Public funding is sometimes a start, but it's not what produces the products

I spent a few days late last year learning to pronounce Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez’ name, as she is clearly someone who will matter in the next few years. Fortunately, her Twitter handle has become a convenient substitute way to refer to her — AOC. I’ll use that for this post.

However, nobody’s perfect, and AOC is plunging ahead actively, and making a few mistakes along the way.

At a hearing late last month on the pharmaceutical industry and drug pricing, AOC questioned Aaron Kesselheim, MD, JD, MPH, an Associate Professor of Medicine at Harvard Medical School and a faculty member in the Division of Pharmacoepidemiology and Pharmacoeconomics in the Department of Medicine at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, about drug development.

Her questioning reminded me of a refrain publishers have been hearing for years:

AOC: Would it be correct, Dr. Kesselheim, to characterize the NIH money that is being used in development and research as an early investment? So the public is acting as an early investor in the production of these drugs. Is the public receiving any sort of direct return on that investment from the highly profitable drugs that are developed from that research?

AK: No, in most cases there is – when those products are eventually handed off to a for-profit company, there aren’t licensing deals that bring money back into the coffers of the NIH. That usually doesn’t happen.

AOC: So the public is acting as an early investor, putting tons of money in the development of drugs that then become privatized, and then they receive no return on the investment that they have made.

AK: Right

The questioning went viral via a tweeted video clip (screenshot below). Notice the framing leaves no room for debate — the public funds drug research. Also, note that as of February 6th, this video had been viewed 2.1 million times. It had also been “liked” 24K times and retweeted 9.6K times.

Derek Lowe, writing in his excellent “In the Pipeline” blog, which covers drug discovery and the pharma industry via Science Translational Medicine, takes a dim view of AOC’s simplistic argument:

I have written many times about the persistent idea that pretty much all drugs are discovered either at the NIH or with NIH funds, whereupon Big Pharma comes in, scoops them up for beads and trinkets, comes up with a catchy name and goes off to reap the big tall stacks of cash. I would say that the exchange above reflects this view, albeit with a bit less vivid detail.

It’s wrong. I know that this picture of the drug-discovery process is just irresistible catnip to some people, but it’s wrong. Here’s why, and here‘s why, and here’s why, and here’s why, and here‘s why again. I’m not saying that there are no drugs that have been born in academic labs, of course – there certainly have been (for a look at one, try Lyrica/pregabalin). But as one of those links details (in an analysis of the 1998-2007 period), such drugs are definitely a minority. This fall I will (I hope) celebrate my 30th year of doing drug discovery research, and never once have I worked on a project where the chemical matter came from an academic lab. You can, in fact, buy entire books that teach academic labs what drug development is really like.

Identifying an interesting protein or cellular pathway, which is what academia does very well, is not inventing a drug. And even on those occasions when an academic lab has identified new chemical matter, a hit in your screening assay is not a drug, either. I’ve gone into detail about the steps in between, but let me just say that I have spent my whole career, one way or another, on just those steps. So when I hear people acting as if none of that exists, that the process is NIH-to-marketed-drug, then I get a bit worked up.

Lowe also points out that if you want a sophisticated understanding of why drug prices are how they are, there’s a long piece by Jack Scannell in Forbes about how and why pharma is able to and has to price its drugs as it does (summary: he argues it’s not cost recovery or value, but a unique access to special lottery tickets that don’t win often, which means each time one hits, the payout — which pharma can control more or less — can be, and maybe has to be, huge).

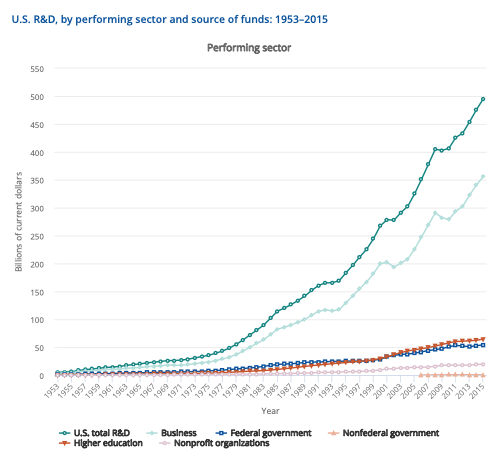

In the most recent “Science and Engineering Indicators (2018)”, business still expends far more on R&D than government, academia, or any other source.

Expenditures like these show how vital businesses are to the extension and application of government funding, as well as providing funding of research and development independently.

This is somewhat reminiscent of the argument that academics and researchers do all the work to generate papers others want to read, and the publishers exploit this work to obtain obscene profits.

If the reports generated by academics were truly what people wanted, then all the government-funded research reports that are publicly available would be very popular. But busy scientists, physicians, and professionals in various fields want more — they want signals about relevance, quality, novelty, and priority from a journals system they know and trust, and they want some level of assurance that what they’re reading isn’t going to be a waste of time, wrong, biased, or some combination of the three. They want professionally produced papers. They want assurances of disclosure. They want editors and publishers who work on their behalf.

I’ve shared Lowe’s exasperation when it comes to arguments like “publishing is just a button,” or assertions that amount to portraying a publisher as an entity that does nothing more with papers than “scoop[ing] them up for beads and trinkets . . . and go[ing] off to reap the big tall stacks of cash.” (There are at least 102 reasons why this is wrong.)

The concepts underpinning any business — pharma, publishing, you name it — are risk and complexity. Drug discovery is far more complex than just identifying interesting chemical or biological candidates, just as publishing is far more complex than just producing a research report.

But the risk aspect is what’s particularly salient here, and the one that seems the most elusive.

Pharmaceutical companies court major risks in order to potentially get multi-billion-dollar drugs on the market. Publishers court far smaller risks — but risks nonetheless — in creating and publishing books and journals. Do all the books and journals sell perfectly? Do they all make money? No. Do publishers have to invest for years before they see a return? Yes. Is there a huge cost in rejections that readers help to cover but never really see? Absolutely. Is every budget year fraught with uncertainty they have to manage reactively or proactively on a consistent basis? That’s an affirmative.

Therefore, my definition of a publisher is simple:

Publishers invest and take risks on behalf of authors.

Lowe is correct to criticize AOC for her oversimplification of the drug discovery process. I urge you to read his entire post, for it is per usual excellent, informative, and concise.

Like Lowe, “when I hear people acting as if none of that exists, that the process is NIH-to-[final-paper], then I get a bit worked up.”

As Plan S advocates and others are I hope slowly learning, publishing is a riskier and more complex endeavor than they might have initially hoped or believed. The ways that publishers extend, expand, enhance, and support effective government research funding aren’t trivial. It isn’t right to trivialize the expenditures businesses make in support of research, researchers, and knowledge pursuit — whether non-profit publishers, university presses, or commercial publishers.

Let’s show some respect and humility for work and expertise maybe we don’t and can’t understand.