Before and After Facebook

An author's excitement about the digital age goes south after social media interposes itself

The following post was written before the openRxiv news or yesterday’s VeriXiv post, which only underscores what a scourge Meta/CZI/Facebook — and funders downstream from Big Tech — have been on the scientific information ecosystem.

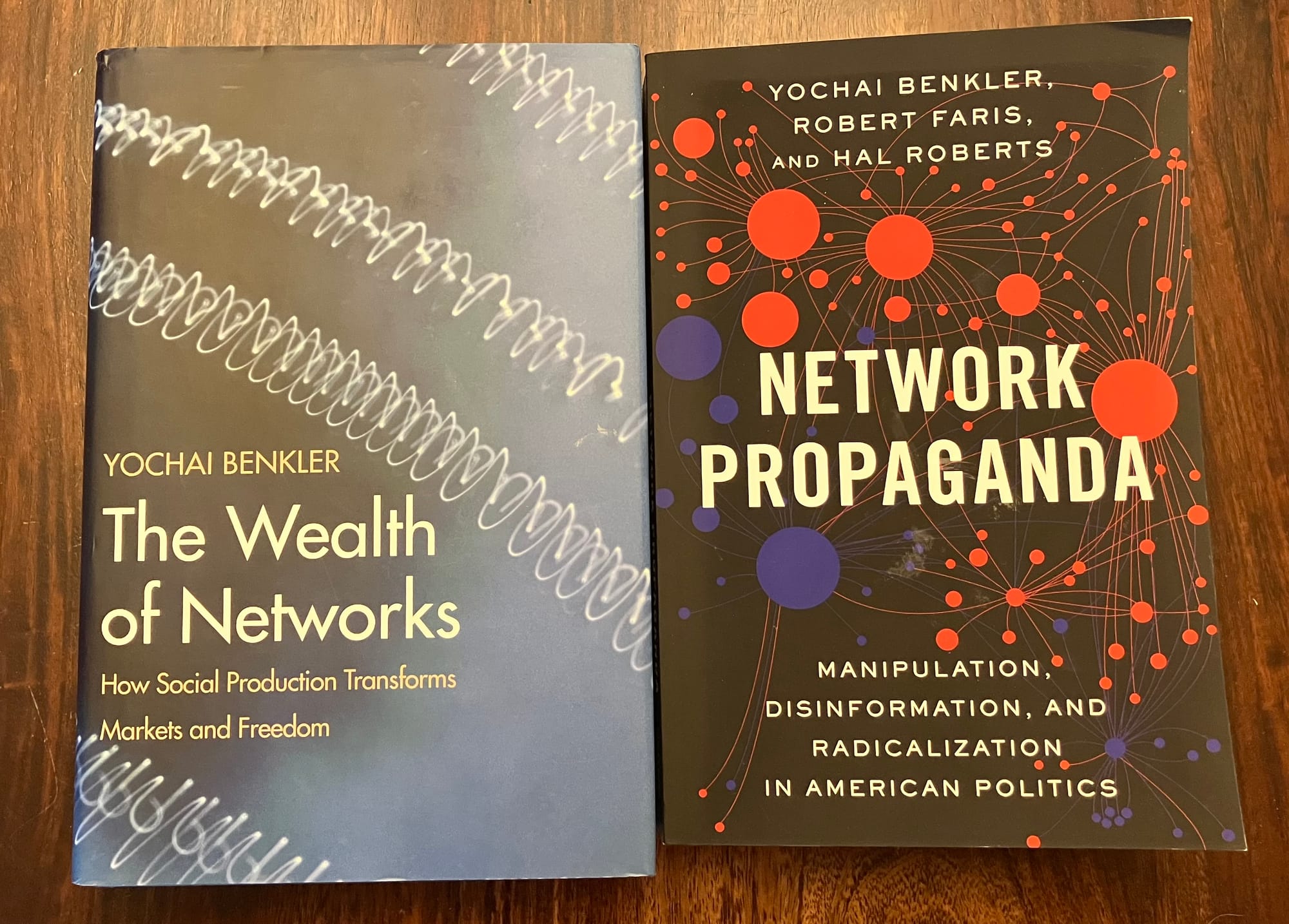

A renovation project has forced me to move a lot of my books and reshelve them. In doing so, I noticed this interesting contrast between books by the same primary author.

He seemed to completely change his attitude about networked information over the course of a decade or so.

In 2006, networks created “wealth” and “freedom.” In 2018, networks were associated with “manipulation, disinformation, and radicalization.”

What happened?

Judging from the contents, Facebook happened.

We have to turn back the clock to 2006, when social media wasn’t nearly the powerhouse it soon became. There was no iPhone. There was no Kindle. There was no Facebook — at least in any meaningful way. It was just rolling out, and didn’t have many of the features that have distorted the information landscape, nevermind the scale. Instead, we had MySpace, Classmates.com, and some nascent blogging platforms. Otherwise, it was websites and search engines, mainly Google.

Then, the platform era began, and new media titans with algorithms and audiences came to dominate a landscape filled with smartphones. Everyone was available all the time. And with user assent and adhesion contracts, our hopes for an Internet independent of big money interests and media manipulation at a large scale collapsed.

Writing in Platform Capitalism, Nick Srnicek notes that financial responses to the 2008/9 housing crisis and resulting financial collapses around the globe also played a role, with the US government indulging in “quantitative easing” which put more money in play and reduced interest rates, with the UK and EU following shortly thereafter. These low interest rates and ready access to capital gave investors and start-ups what they needed. Bonds being swept off the table caused stocks to become more sensitive to being tickled upward. Suddenly, firms seeking to grow had investors ready to invest because interest rates were low, while the primed stock market let returns follow fast and reach new heights.

Using these examples, I want to make clear that I am not shaming the author, but am praising his excellent observations of the world as it is. The world changed dramatically, and his hard work left striking evidence of this.

2006

Here is an example of what Yochai Benkler wrote in The Wealth of Networks: How Social Production Transforms Markets and Freedom. You can sense a little uncertainty, but the overall tone is positive, as it the book’s hopeful approach:

The basic intuition and popular belief that the Internet will bring greater freedom and global equity has been around since the early 1990s. It has been the technophile’s basic belief, just as the horrors of cyberporn, cybercrime, or cyberterrorism have been the standard gut-wrenching fears of the technophobe. The technophilic response is reminiscent of claims made in the past for electricity, for radio, or for telegraph, expressing what James Carey described as “the mythos of the electrical sublime.” The question . . . is whether this claim, given the experience of the past decade, can be sustained on careful analysis, or whether it is yet another instance of a long line of technological utopianism.

Benkler writes then about how “[g]reater access to means of direct individual communication, to collaborative speech platforms, and to nonmarket producers more generally can complement the commercial mass media and contribute to a significantly improved public sphere.”

He also writes in 2006:

If we are to make this culture our own, render it legible, and make it into a new platform for our needs and conversations today, we must find a way to cut, paste, and remix present culture. And it is precisely this freedom that most directly challenges the laws written for the twentieth-century technology, economy, and cultural practice.

Compare the chapter headings in 2006:

- Peer production and sharing

- The economics of social production

- Individual freedom: autonomy, information, and law

- Political freedom part 1: the trouble with mass media

- Political freedom part 2: emergence of the networked public sphere

- Cultural freedom: a culture both plastic and critical

- Justice and development

- Social ties: networking together

- The battle over the institutional ecology of the digital environment

2018

Now, the chapters in the 2018 book, Network Propaganda: Manipulation, Disinformation, and Radicalization in American Politics. As you already suspect, they are quite different:

- Epistemic crisis

- The architecture of our discontent

- The propaganda feedback loop

- Immigration and Islamophobia

- The Fox diet

- Mainstream media failure modes and self-healing in a propaganda-rich environment

- The propaganda pipeline: hacking the core from the periphery

- Are the Russians coming?

- Mammon’s algorithm: marketing, manipulation, and clickbait on Facebook

- Polarization in American politics

- The origins of asymmetry

- Can the Internet survive democracy?

- What can men do against such reckless hate?

By 2018, Benkler wrote this:

. . . the present source of information disorder in American political communications is the profound asymmetry between the propaganda feedback loop that typifies the right-wing media ecosystem and the reality-check dynamic that typifies the rest of the media system. The most important attainable change in the face of that asymmetry would be to the practice of professional journalism. Our findings make clear that mainstream professional journalists continue to influence the majority of the population, including crossover audiences exposed to both right-wing propaganda and to journalism in the mainstream media.

While Benkler is careful not to blame Facebook entirely for the mess, he does lay a lot of the blame at its feet. Supercharged on smartphones, it became capable of swinging elections and kicking off genocides.

Of course, we made a few changes of our own, mainly pushing preprints to the fore from 2013 onward. This led to a study finding that white nationalists like preprints, and an analysis showing that the alt-right exploits preprints. We have been fueling the same terrible flames with our unprofessional information management approaches. Given that Mark Zuckerberg’s track record, I will ask again: Should bioRxiv and medRxiv walk away from CZI?

A lot has changed in 20 years, and it is accelerating in the wrong direction. What are we doing to pump the brakes?