Colleges & Corruption: It's Complicated

The signals sent by sanctioned corruption might have fostered the admissions scandal

This week’s college admissions scandal has generated a lot of interest and outrage. There’s much to be said about the way university admissions in the US have evolved into a pay-to-play scheme, with various fast-tracks into top schools for people with enough money and connections — all of it condoned, even encouraged.

In the midst of all this, I’ve been looking for a gem of perspective, and Tyler Cowen delivered it:

Of course universities have long taken money to let in unqualified applicants; what is happening here is they are going after the local rate busters.

Cowen’s point is that corruption, bias, and favoritism are know to exist in the college admissions process, but universities don’t want freelancers or scalpers selling off access at higher prices. It’s a cynical and funny perspective, and holds perhaps more than a grain of truth. After all, in a purely economic view, universities can’t let a side economy thrive that might imperil revenue sources of their own.

Then there’s the legal front, which is more flexible than we might like to imagine. We all get signals about what laws we can and can’t break. Police won’t pull you over for going 35 mph in a 25 mph zone in our area. So, we all go faster, knowing that some level of cheating is tolerated. If in doubt, we’ll pace the police cruiser, which is usually also going faster than the posted speed limit.

Signals like this tell us which laws are strictly enforced and which are not. (That said, these people tried to blow through town, and definitely needed to be stopped.) But what about a donor who slaps down $500,000 at the school his child ultimately attends the year she applies? That’s the equivalent of going 35 mph in a 25 mph zone. Everyone knows you’ll get away with it.

For parents seeking to get their kids into universities, there are a lot of legal and acceptable ways to game the system — legacy admissions, donations, paying for test prep, going for interviews, encouraging extracurriculars, getting your kids into sports, making multiple campus visits, securing letters of recommendation, networking with friends and connections, staging mock interviews, and more.

Bias permeates the education system, from disparities in funding school districts for K-12 education to disparities in access to pre-K programs. Race, class, and economic biases warp the system at a deep level. One could argue the system is understood intuitively to be gamed from the beginning — that the point of the system is to see how far you can go before you personally run out of gambits (or interest in playing the game).

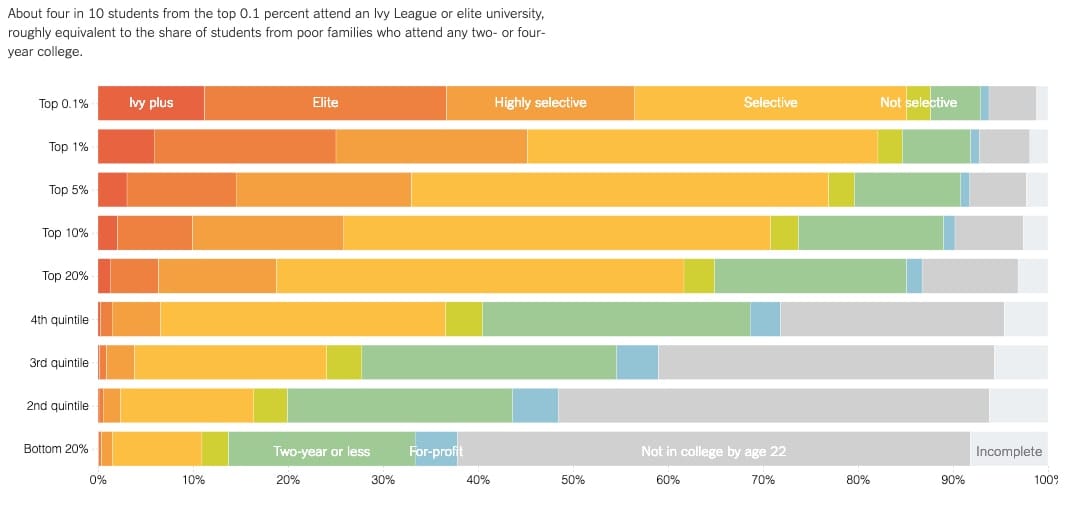

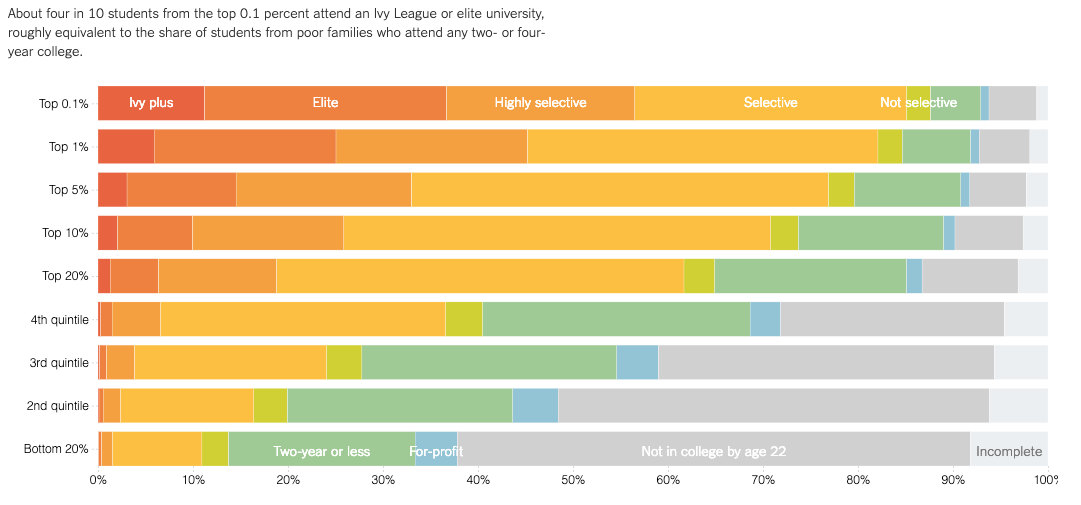

What’s the result of such a system? Kids from the top end of the socioeconomic scale get into top schools far more often. In a 2017, the New York Times analyzed some trends. At 38 universities in the US, more students came from the Top 1% economic bracket than from the entire bottom 60% — including Yale, Tufts, and other Ivys. Opportunity does not seem to be reapportioned through education, with hardly any students outside the Top 20% getting into Ivys and Elites. The trend is pretty obvious — the class system becomes the education system, which reinforces the class system:

Most parents who experience getting a child into college come out feeling like the system is a game, and can sense which levers they can pull and which are out of reach. And while the parents and coaches and proctors in these cases went way out of bounds, the field of play isn’t level in the first place. Corruption begets corruption.

The other question that seemed to leave people scratching their heads was around how these unqualified students might fare. As Cowen writes in a Bloomberg essay:

First, these bribes only mattered because college itself has become too easy. . . . If the bribes allowed for the admission of unqualified students, then those students would find it difficult to finish their degrees. Yet most top schools tolerate rampant grade inflation and gently shepherd their students toward graduation. That’s because they realize that today’s students (and their parents) are future donors (and potential complainers on social media). It is easier for professors and administrators not to rock the boat. What does that say about standards at these august institutions of higher learning?

That’s another aspect of the corruption of the university to drive sales and marketing — once you’re in, you are virtually assured of getting through if you are willing and able to pay. It seems the only certain way to not complete college is to stop paying tuition.

While it’s easy to point at the perpetrators in the FBI investigation, the problems are larger and deeper — a corruption of a supposedly egalitarian and meritocratic education system by money, advantage, race, and class.

When it comes to how the US educational system has become corrupted by interests that go beyond its intended purposes and stated ideals, the current scandal seems pretty clear cut. But when you start to look for a part of the system that isn’t distorted by bias or corruptible elements — well, it’s complicated.