Will the Taxman Come for Non-profits?

Loaded NFPs will need to re-examine tax and "generational equity" theories

Many non-profits push retained earnings into long-standing investment funds with nary a thought — often to such a degree that they have become players in the financial markets far more than they are stewards of a social mission.

When revenues become dependent on the returns from these investments, even just a little bit, such non-profits see their story start to merge with a larger narrative around income inequality, which was recently outlined by Scott Galloway in an interview in New York magazine, where he notes:

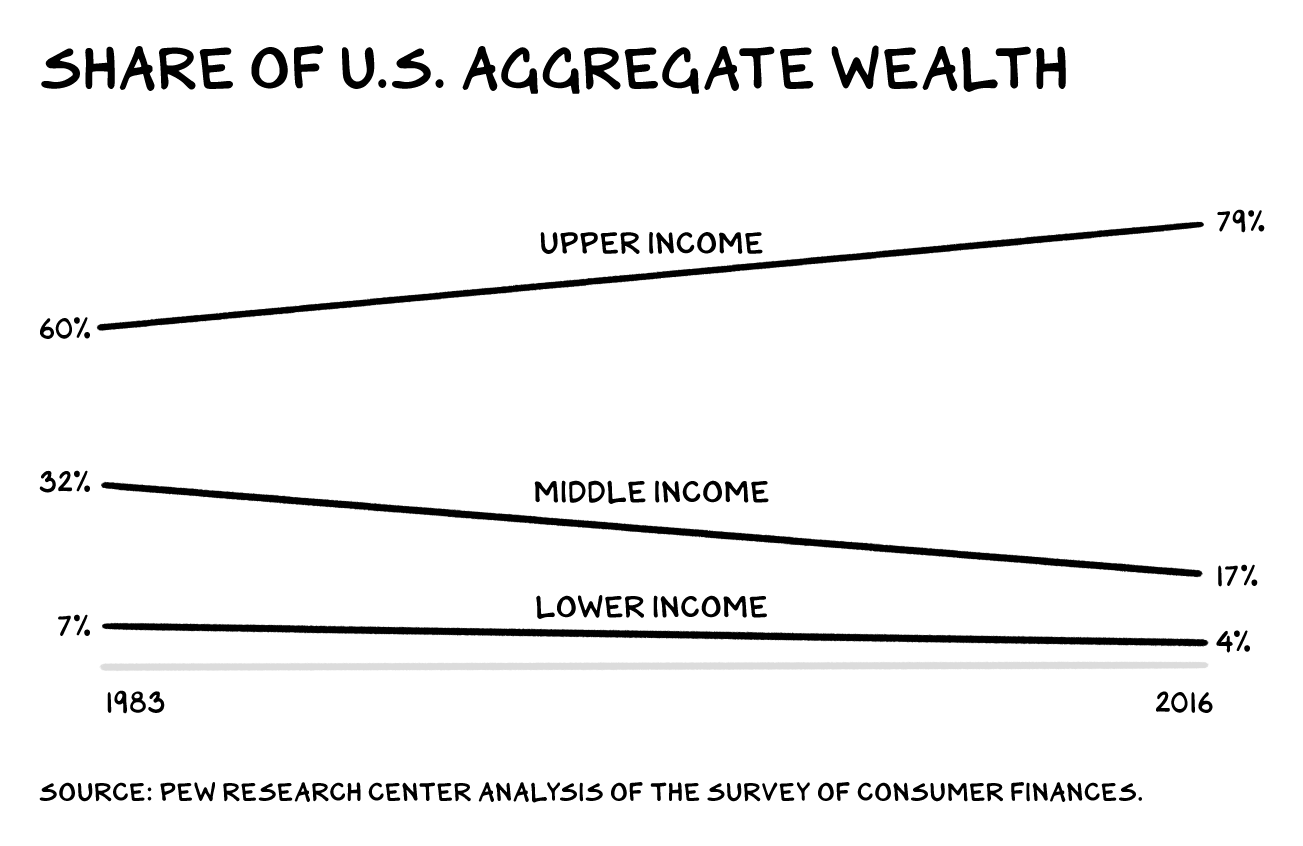

. . . for the past 50 years in America, we have decided to transfer wealth from the middle class to the shareholder class. . . . the share of income controlled by the top one percent has exploded. And I think that creates all sort of externalities.

By injecting retained earnings into the financial markets, non-profit societies and universities are blending with the shareholder class, even as they pare their staffs and outsource functions to preserve or improve their margins.

This isn’t sitting well with some, as noted by the recent agitation at Duke University Press (DUP) about a potential move to unionization, as well as other pro-worker wage, union, and equity movements around the world.

Then, there is the taxman, who is lurking in national, state, and local governments, watching these accounts swell and split from their mission-centric purposes.

To see the degree of dependency on the financial markets among non-profits, I analyzed a dozen to see how their revenues, net assets, and investment income changed between 2001 and 2018. In short, these entities have become more dependent on investment income as a source of revenues, and have in aggregate let their net assets (i.e., retained earnings) eclipse their annual revenues. Revenues are only 4.4% the size of one organization’s retained earnings.

What does this mean? It means we have non-profits that don’t put their money where their mouth is, so to speak. And if you follow the money, more and more of it leads to an index fund or money manager, not to social programs, business investments, strategic initiatives, or higher wages and better benefits for employees.

But first, the larger picture, courtesy of Galloway’s “No Mercy/No Malice” newsletter, where he’s outlined trends in income distribution and share of wealth by age:

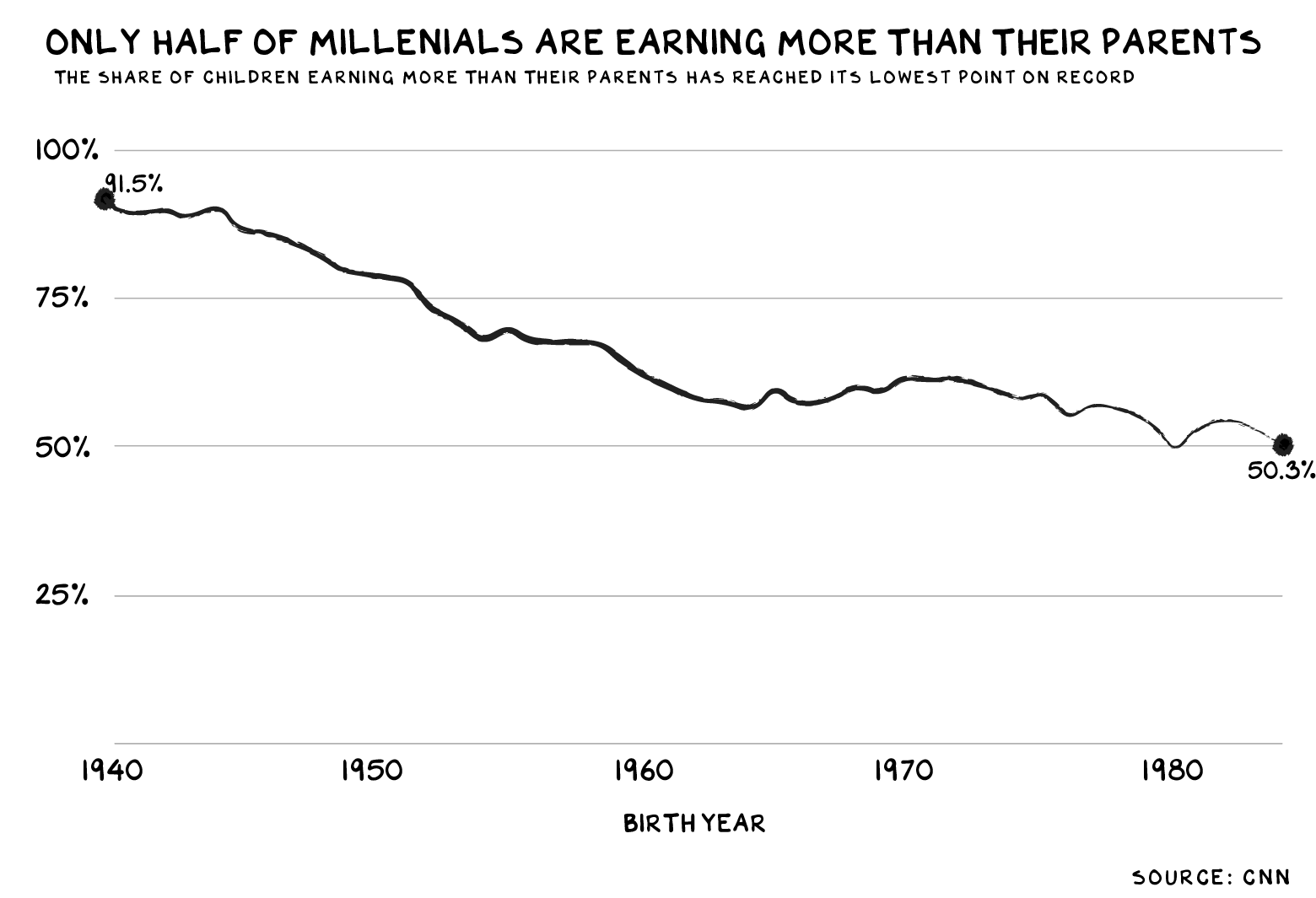

Galloway feels that the social unrest we’ve seen the past few years — and are likely to continue to see — is an externality of all this money locked up in financial investment instruments. Young people without jobs or connections to communities are more easily radicalized, after all. So, from the GameStop stock pump and dump to strikes to protests of various kinds, social injustice and financial injustice are stoking young people to demand change, with the financial injustice perhaps not as widely acknowledged:

Young people want volatility. If you have assets and you’re already rich, you want to take volatility down. You want things to stay the way they are. . . . People under the age of 40 are fed up. They have less than half the economic security, as measured by the ratio of wealth to income, that their parents did at their age. Their share of overall wealth has crashed.

The non-profits analyzed cut across fields. I did focus on those that took PPP loans last year — they’re marked with an asterisk (*). They are noteworthy, as the investment funds of these organizations have likely increased significantly in value as the stock market has surged in the wake of the PPP loans (and more recent stimulus), meaning organizations taking PPP loans have probably benefited at least twice.

The dozen non-profits I analyzed are:

- American Chemical Society

- IEEE

- AAAS*

- American Academy of Pediatrics*

- American Society of Mechanical Engineers*

- American Antiquarian Society*

- American Association for Cancer Research*

- American Association of Critical Care Nurses*

- American Diabetes Association*

- American Philosophical Society*

- California Academy of Sciences*

- Cold Spring Harbor Labs

Across these organizations in 2001, revenues were 108% of their net assets, meaning they were generating more revenues annually than they held in retained earnings. They were more business than bank. Also in 2001, investment income — dividends, interest, and other payouts from financial market investments — represented 13.7% of their overall revenue.

In 2018, revenues had slipped below the retained earnings waves, representing 91.5% of their net assets, while investment income had risen to 16.5% of their revenues.

These are rich organizations. Between 2001 and 2018, the average net assets across this group rose from $143 million to $284 million. Annual revenues also rose from $93 million on average to $179 million. Investment income alone rose from $4.7 million to $13.8 million on average for the group.

Justifications for holding on to such large retained earnings and investment funds often focus on a rather weak concept called “generational equity” — the notion that the next generation should benefit from the organization’s strengths and history as well, which means saving enough money to ride out the rough times to ensure the organization doesn’t collapse.

Sounds a lot like: “If you have assets and you’re already rich, you want to take volatility down. You want things to stay the way they are.”

Also, more jobs and higher pay may be viewed as more legitimate “generational equity” by young people wanting opportunities and success.

How legitimate is it to have these big stockpiles of investments? Recalling events from 2001 to the current day, and you can see many that might have represented a need for reserves — terrorist attacks (9/11 and 7/5) and a global war on terror; the 2009 financial crisis; and a major pandemic. Add into this the challenges of digitization, open access, and refactoring processes and infrastructure, and you might expect to see reserves tapped and organizations struggling across these 18 years. Yet, these organizations weathered the various sources of tumult with few apparent financial problems. In fact, they grew richer, and now have the bulk of their money in the bank instead of in the business.

There are three organizations that jump out as nearly pure investment funds, with small businesses operating out of them. But first, an overview of the firms that are more typical from the set of 12.

Businesses with Banks

With three exceptions noted below, the group generally looks like businesses with banks. However, the cut point is unclear. Is Cold Spring Harbor Labs, with 32% of its money coming from revenues (including 10.1% from investment income) a viable business, even if its “bank” component is 68% of its financial footprint? I’ll let you decide (all data from 2018 990s) for organizations with their revenues reaching at least 20% of their net assets — a very low bar, I think:

- American Chemical Society — Revenues were 66.5% of its net assets

- IEEE — Revenues were 124% of its net assets

- AAAS — Revenues were 98.7% of its net assets

- American Academy of Pediatrics — Revenues were 203% of its net assets

- American Society of Mechanical Engineers — Revenues were 105% of its net assets

- American Association of Critical Care Nurses — Revenues were 36.3% of its net assets

- American Diabetes Association — Revenues were 269.2% of its net assets

- Cold Spring Harbor Labs — Revenues were 31.8% of its net assets

While IEEE has grown a great deal since 2001 — revenues increasing from $213 million to $547 million in 2018 — its revenues are 124% of its net assets, meaning it is far more of a business than a bank. The same can be said for the American Academy of Pediatrics, which has revenues that are more than 2x the amount of retained earnings and investments its sitting on. And the American Diabetes Association also falls into this category. The others may have their decisions influenced heavily by banking decisions, given that the majority of their assets in any year are in the markets.

Banks with Businesses

Three organizations — the California Academy of Sciences, the American Philosophical Society, and the American Antiquarian Society — jump out as being banks far more than they’re businesses. Each took a PPP loan, it should be noted.

- The American Antiquarian Society’s revenues are only 14.9% of their net assets for 2018 ($13 million in revenues against $87 million in net assets). More than $5.3 million of the $13 million in revenues came from investment income, meaning that non-investment revenues are ~10% of their assets.

- The American Philosophical Society’s revenues in 2018 were only 4.4% of its net assets ($9.0 million against $207 million in net assets). Fully $6.7 million of the revenues came from investment income, meaning that business income was around $2.3 million, or just over 1% of net assets. That makes this 99% a bank.

- The California Academy of Sciences’ revenues are only 14.6% of their net assets for 2018 ($74 million against $510 million in net assets). More than $15 million of the revenues came from investment income, meaning business generated around $59 million, or about 10% of net assets.

In all three cases, these non-profits could be plausibly described as 90-99% banks rather than mission-driven non-profits or businesses. What do you think consumes most of the attention their CFOs and Boards? The 90-99% of the money? Or the 1-10% that still functions to support the mission on an active annual basis?

What does this all mean? I predicted last year that one consequence of the Covid-19 pandemic may be that non-profit investment funds could be subject to new taxes, noting that in 2019 this barrier had already been broken around Harvard University. This is part of a longer-term trend. In 2016, Princeton had to pay $14 million after licensing profits were claimed as tax-free due to the university’s non-profit status, leading one resident to call Princeton “a hedge fund that conducts classes.” And there’s more simmering — in Arizona, Pennsylvania, Illinois, and California, as residents start to bristle at rich, tax-free universities playing fast and loose with norms and rules to make themselves richer, while local communities decay and see their taxes increase. The universities are throwing their tax-free statuses in the collective face of surrounding communities, and people are increasingly fed up.

I think more volatility is coming for non-profits and universities with fat endowments. Pre-pandemic estimates showed taxes on large university endowments were lower than anticipated, but this is likely to change. Someone has to pay back the borrowing and debt incurred by the pandemic, infrastructure investments, and otherwise, and the investment funds of universities and non-profits look plump and don’t make much sense.

I can’t see much sympathy being generated for some of the non-profits here and elsewhere sitting on huge investment funds. When the taxman comes, expect some young voices to be cheering him on.

Related Note — Non-profits that had donated to politicians who disputed the 2020 election results appear to have quietly shifted their political donations away from such politicians and toward more mainstream candidates and PACs. It’s still early, but the trend seems real. More to come as warranted.