Two-Faced Information Systems

Information spaces split their personalities — including scholarly communications

The prime examples of the two-faced information environment are the big social media companies, who were recently caught in the inevitable epistemic vise. Their solution? Dramatic deplatforming decisions as they responded to a rapidly escalating crisis caused by forces they’d been feeding, ignoring, and downplaying for years. But theirs is not the only two-faced information environment. Such things exist in more and more places — we have one of our own, as well.

But first, to the Prime Suspect, Facebook, which keeps saying one thing and doing another — pledging moderation, claiming standards, and promising to improve. The company has made some changes, but grudgingly. Banning Holocaust denialism took them years, for instance.

Facebook is not all bad, not by a mile. It connects families and friends in good ways, and it supports social causes, artists, makers, hobbyists, communities, and small businesses. It helps towns preserve a sense of community. It can be fun — less so the past few years, but if you manage things well, it still can be enjoyable.

Yet, it’s swath of destruction is wide, long, and consistent, bringing us to this January’s traumatizing injuries to the American psyche and the world’s most successful democratic republic.

As a refresher, here are a few things Facebook allowed which steered events as we moved toward the deadly and destabilizing January 6th insurrection.

In August, Facebook was used to mobilize white nationalist militias into Kenosha, WI, after protests erupted in the wake of the police shooting of Jacob Blake, a black man. The police had shot him seven times in his back, and local protests followed. Calls for militia groups to go to Kenosha posted on Facebook were reported to moderators 455 times, and cleared by four moderators as not violating the rules before they were finally removed.

Kyle Rittenhouse, a 17-year-old, responded to the calls. The Facebook posts weren’t removed until hours after Rittenhouse had allegedly shot and killed two people. He’s currently out on bail, and was caught on camera recently posing with members of the Proud Boys, flashing white supremacist signs, and breaking his bail agreement by patronizing a bar.

In November, Steve Bannon suggested on Facebook that NIAID Director Anthony Fauci and FBI Director Christopher Wray should be beheaded. Zuckerberg told staff at a company meeting these comments were not enough of a violation of Facebook’s rules to permanently suspend Bannon, even though he was permanently suspended from Twitter for the same statements.

Also in November, data from Facebook’s own analytics system showed lies about the election were spreading fast, especially in groups, yet the company sought to downplay or dismiss the assertions. While it banned political ads for a time, it was the content that was finding and affecting users.

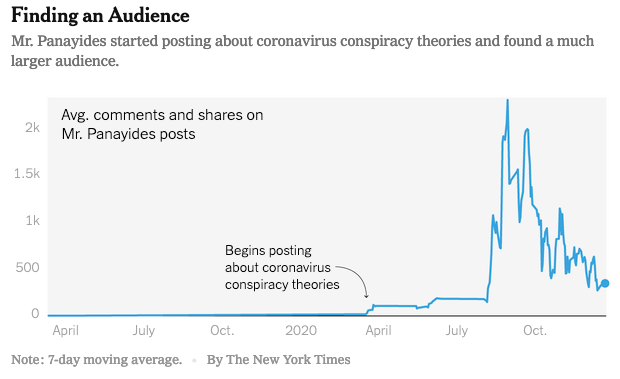

A fascinating report with excellent info-graphics in the New York Times illustrates how users were gradually radicalized on Facebook — one year, posting harmless selfies and receiving a few “likes,” and then being heavily rewarded with more “likes” as their posts became more radical and disengaged from reality:

Fast forward to January 2021. In the wake of the Capitol insurrection, Facebook’s COO Sheryl Sandberg sought to downplay the company’s role in spreading lies about the election, fomenting of conspiracy theories, and coordinating planning for the invasion of the Capitol:

I think these events were largely organized on platforms that don’t have our abilities to stop hate, and don’t have our standards, and don’t have our transparency.

But, as Sandberg was making these statements, others were documenting activity on Facebook and Instagram, with David Gilbert from Vice noting:

. . . at the very moment Sandberg made these comments, there were at least 60 “Stop the Steal” groups active on Facebook, some with tens of thousands of members and millions of interactions. And hours before Sandberg spoke, Ali Alexander, the self-described organizer of the Washington protest last week, was openly posting about further threats to come on his Instagram account . . .

Facebook was also caught showing military gear ads next to content peddling election misinformation and discussing the failed coup attempt.

Not that Facebook didn’t make some efforts — it’s what two-faced providers do. In October, Facebook banned QAnon, in September, the company removed more than 6,500 militia group pages from its platforms, and in June so-called “boogaloo” white supremacists groups were deplatformed.

But, even now, “Stop the Steal” groups can still be found on Facebook.

Facebook’s two-faced approach to information and moderation — trying to present an acceptable face to the public to conceal the rot and malice lurking just beyond — has modeled the way for many others to accept such ruinous information habits.

Not that Facebook was first. The two faces of information have been readily apparent on Fox News for decades, with a news division that is genuinely interesting and an “opinion” side operating as nothing more than a disinformation and propaganda machine. On election night, these two were in open conflict, as the news side called Arizona for Biden, surprising the propagandist side of the house and infuriating the Trumps, according to reporting from Axios.

As the media is divided, so follows reality.

Scholarly communications has become divided as well — a new situation being actively exploited by the disreputable side of the divided general media environment. Our new, lax side feeds them. The right-wing media are oversampling from it, as are white nationalists. We’ve even created safe havens for alt-right misinformation, with CERN’s Zenodo actually defending the right of conspiracy theorists to publish misinformation on their servers — not once, but twice.

Add to this the problem of predatory publishers, and our trusted face has a new, potentially decrepit counter-visage — much like the rest of modern media.

In some ways, the duplicity of the large commercial information purveyors like Facebook and Twitter is rational — their goal is not so much ideological as financial. That is, it’s not creed, but greed. They want to be rich, they found a great way to mine our attention, and now they’re billionaires. So far, so clear.

But what about us? What’s our motivation for leaving unreviewed preprints up, supporting a business model that enables predatory publishers, or defending conspiracy theorists’ and bad-faith authors’ rights to post whatever they want on our platforms?

Since it’s not greed we’re pursuing, what are we pursuing with these choices? “Open”? “Free speech”? Silcon Valley envy?

Are we the ideologues?

Change is coming. At this point, it must. A great nation experienced an insurrection as a result of a poisoned and sloppy information space. History shows us a path. After traumatic events involving food safety, drug safety, and public safety, regulation swooped in to address the problems. We have food handler permits, drug recalls, and safety belts, for example.

We are now realizing that information safety is also vitally important. There is no reason to accept unnecessary trade-offs. EU lawmakers may be the first to move. The Rector Magnificus of the University of Amsterdam, Professor Karen Maex, has called on European Commissioners to propose a “Digital University Act,” noting via reporting that:

. . . private companies are continuing to expand their role while the public character of our independent knowledge system is further eroded.

Interviewed yesterday in the Boston Globe, Lawrence Douglas, professor of law, jurisprudence, and social thought at Amherst College — and one of the first people to publicly predict Trump would attempt to overturn the 2020 election results — said the US is still vulnerable to political lies, noting:

. . . it’s not just our electoral system. It’s our political system writ large. We need to find ways to control the conspiracism. . . . You need to have curators of information. A democracy can only survive if people make informed choices. And people can only make informed choices if their source of information is reliable. And if their source of information is unreliable, and full of falsehoods and conspiracy theories, then inevitably people are going to make bad decisions and choose demagogues.A big part of re-establishing a trusted, independent, and reliable information system will revolve around establishing higher standards of quality. This will mean we will need to stop pretending that there are no consequences for playing fast and loose with information.

We know better. To pretend otherwise would be . . . well, talking out of both sides of our mouth.