Why Aren’t APC Payers Disclosed — Part 2

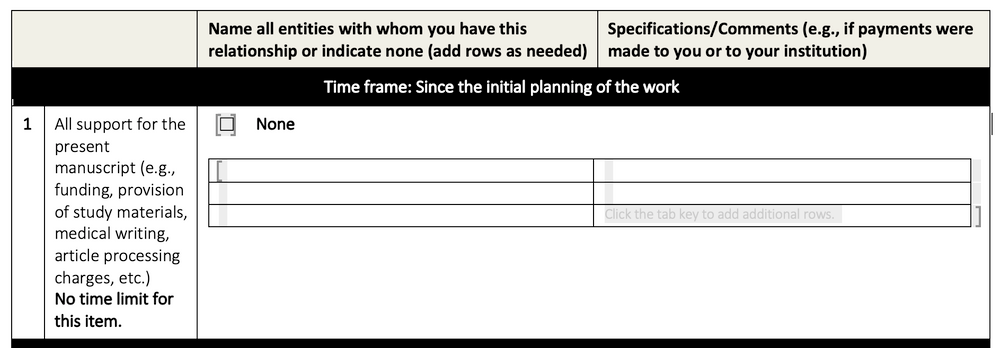

In 2021, the ICMJE extended and refined author disclosure requirements to include additional elements of support behind a published article — funding support, medical writing, and article processing charges (APCs):

Yet, publishers who claim to be compliant with ICMJE policies have never created a way for APC disclosures to be presented to readers. Many seem unaware of the new requirement, or uninterested in collecting and sharing such information in a systematic manner.

Extending disclosures in this manner makes a lot of sense. Transparency and accountability matter. If corporations are paying APCs, and doing so in a systematic manner, that’s potentially worth tracking and inquiring about. Publication planning based on APC spending has been a well-known practice for years, and disclosures would bring it further into the light. If research is funded by government agencies but the APC paid by a private company, that’s worth revealing for similar reasons. If the authors themselves have paid a share of the APC out of personal funds, that’s worth knowing. If a waiver was granted, that’s worth knowing, too.

Without clear disclosure of who paid the APC, I find templated statements like, “The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript” a little harder to swallow. If the funder approved the APC spend after the manuscript was prepared, that statement is shaky at best — after all, editing or self-editing can both be caused by funder APC payment involvement.

Disclosing who paid the APC provides good information about a specific paper, and potentially more valuable information in aggregate across publications and over time. This information could be useful to authors and readers simultaneously.

There are, of course, disincentives to disclosing such information:

- APCs are viewed by some as purely good things, enabling free access, and for these people — mainly OA advocates, I’ll assert — APCs don’t fall into the sphere of potential influence or “putting a thumb on the scale.”

- Showing that someone paid an article’s publication charges might look bad, discouraging utilization of OA by funders or authors who don’t want to have to explain who paid — or how they paid — their APC.

- Disclosing APCs may make OA articles look more like vanity publications.

- We simply haven’t thought hard about it.

There are, of course, good reasons to disclose APC payers:

- The integrity of OA journals. Disclosure of APCs might be another way to separate legitimate OA journals from predatory OA journals. That is, if there is an APC disclosure of this kind required of authors, they may feel more assured they’re in better hands than if the publisher doesn’t abide by this type of transparency.

- Giving credit where credit is due. Disclosure is becoming more important as APCs rise, and as OA becomes a more central mode of publishing research content. The entity who pays to make it freely available may want credit — entities such as Research4Life, institutional payers, or granting entities.

- Transparency for readers and users. Simply put, the reader may want to know who paid not only for the research, but for their access.

- Ensuring ethical integrity and allowing for ethics interrogation. The ethical aspects of making something freely available may matter in particular cases and more generally. If we see that a certain corporation or set of individuals is providing APC payments — not research funding, but the funds to make content available without a paywall — our perceptions of their motivations may shift, our interest may be piqued, and inquiries might become appropriate. Without disclosure, we’re in the dark. We don’t know if ACME International is providing APC funding for a set of authors with government research grants across a swath of OA journals.

- Making life harder for predatory publishers and paper mills. Disclosing who is paying the APC is a step that predatory publishers might not want to take for a variety of reasons, and one that paper mills might find difficult to surmount. An ethical, transparency barrier is a good thing to interpose on these players.

- Because we might learn something. Who is funding APCs is potentially useful information for analyses, such as which entity is the largest payer of APCs, and how APC expenditures may compare with research expenditures, mission and purpose, and so forth. Wouldn’t it be fascinating today to look back at nearly 20 years of PLOS or BioMedCentral APC disclosures, and compare their geographic, financial, and trend data?

The lack of disclosure is especially odd given that APC payer information is perhaps the most verifiable information available — after all, the publisher receives either invoicing information or actual payment from some entity prior to publication, making the inclusion of this information a simple matter.

I wrote about this approximately a year ago, and continue to be puzzled as to why journals are not disclosing this information. So, I’ve started to ask.

- At JAMA, the staff spokesperson asserted — with what struck me as false sophistry — that knowing who paid the APC isn’t really all that important.

- At BMJ, the editor who answered has no involvement with APCs, so kicked the question to staff, who are on Easter holiday.

- CMAJ Open did not respond to my inquiries in time for this post.

- The British Journal of Psychology Open did not respond to my inquiried in time for this post.

Other inquiries are out, but the lack of interest in the topic is notable across the board. As some editors have noted, few want to rock the OA boat these days.

Yet, any time money touches an authorship group, a research report, or a publication event, it has the potential to exert influence. Knowing who is paying APCs — both specifically and generally — can only spread light and increase transparency.

Why are we hesitating?